JSNA Live Well - Healthy lifestyle and behaviours

1. Health Behaviours and Lifestyle

This JSNA Chapter presents data around healthy eating, good nutrition, physical activity and those groups in the Borough which need targeted support. Please note further information and more detail around these topics can be found elsewhere in the relevant sections of the JSNA.

1.1 Introduction to Health Behaviour

Human behaviour and lifestyle factors can affect every aspect of health and wellbeing both favourably or unfavourably and to a different degree throughout an individuals’ life. Lifestyles and health behaviours are complex and influenced by multiple factors including genetics, wider determinants of health, previous experiences throughout life, the environment, societal factors, cultural factors as well as individual and interpersonal factors. Therefore, the misconception that individual’s behaviour is due to ‘choice’ alone, over-simplifies our understanding.

When considering health behaviours and lifestyle, it is helpful to think of health and wellbeing on a dynamic continuum over the life course. While the degree of influence and need for intervention will vary based on individual circumstances and need, the fundamental components of a healthy lifestyle are relevant to all individuals, irrespective of health and wellbeing status and can favourably influence health and wellbeing at all life stages. Therefore, the potential benefit of healthy lifestyle behaviour change should not be under-estimated.

National evidence suggests that a quarter of England’s adult (age 16+) population engage in three or more behavioural risk factors 1. The Wandsworth Joint Strategic Needs Assessment 2017/18 and Annual Report of the Director of Public Health 2017/18 2, highlighted a number of Wandsworth residents engage at least one behaviour that can have a detrimental impact on their health.

Based on most recent data, 7.8% of adults in Wandsworth are smokers 3, 1.5% of adults in Wandsworth are estimated to be dependent on alcohol 4 and 15.8% of people in Wandsworth are physically inactive, completing less than 30 minutes of physical activity per week.

Though we are unable to ascertain how many residents engage in multiple behavioural risk factors based on local data, current evidence suggests these behaviours tend to cluster together, creating multiple risk factors for poor health 5. Based on national estimates and the current population in Wandsworth (aged 15+), it would be expected that around 76,700 residents engage in three or more behavioural risk factors. The health of people of Wandsworth is generally faring better than the rest of England.

These behaviours are all modifiable have the potential to improve multiple areas of health and wellbeing for the residents of Wandsworth such as reducing the impact of and preventing long term conditions, improving mental health and wellbeing of residents and encouraging social connectedness of residents in the borough. Whilst there is good work happening across the borough and evidence of good practice, numerous residents are engaging in behaviours that are detrimental to health in both the short and long term or exposed to environmental and metabolic risks for poor health. This chapter considers the contribution of lifestyle and health behaviour on the health and wellbeing of the residents of Wandsworth based on current evidence and local data.

Life expectancy at birth for men and women of Wandsworth is 80.6 and 84.2 respectively, higher than national figures. Healthy life expectancy at birth for residents is also higher than the national figures for both men, at 62.7 years, and women, at 68.1 years. However, there are areas for improvement.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lifestyles, health behaviours and health and wellbeing of local residents remains unclear. However, the need for supporting residents in improving physical and mental health, in part with promoting and facilitating healthy behaviours is a priority in light of the tragic COVID-19 pandemic.

Health Behaviour Across the Life Course

Making healthy lifestyle changes has the potential to reduce risk of developing long-term conditions, improve health and wellbeing and also improve health and ability to function independently in later life. Evidence suggests that behaviour change is both easier to achieve, more cost-effective, gives a greater return on investment and is more likely to be long-standing if established early in life 6.

Throughout the life course, from preconception to end of life care, all individuals are vulnerable to the risks posed by health-harming behaviours and environments. Children and elderly people are at increased risk from poor health behaviours and therefore are more vulnerable to risk factors that contribute to poor health and wellbeing and ultimately chronic conditions.

Within the first two years of life, a child’s absorbs new information and learns from and adapts to its surroundings. This process is influenced by diet, relationships, stress, socio-economic status and physical activity – all of which form the foundations for a child’s cognitive development and affects not only their health and wellbeing, but all areas of learning including social and intellectual development. Parents, families and caregivers are, of course, crucial for shaping childhood behaviour and healthy, or unhealthy, behaviour. Behaviour in childhood lays the foundation for behaviour in adulthood, for example, those who are physically active in childhood are much more likely to be physically active as adults.

This is relevant to residents in Wandsworth. The latest available data comes from the Active Lives Children and Young People Survey, Sport England; in 2020/21 the proportion of physically active children and young people was 63.0%, in comparison with the London average of 44.4% and the national average of 44.6 % 7. Based on evidence that physical activity declines with age, this behaviour is likely to decline into adulthood and can lead to intergenerational behaviours of physical inactivity passing through families.

In Wandsworth 17.4% (n=57,783) of the total population are under 18 in 2023, with a third of all households containing children. The population of 0–17-year-olds is projected to decrease by 9.6% by 2041 (from 57,783 in 2021 to 52,257 in 2041) 8. The population aged 10-24 years experiences a range of changes in lifestyle with associated behavioural, emotional and social changes; it is at this age in which life-long health behaviours tend to become set in place, which provides a unique opportunity to intervene and promote healthy behaviour within this age range with the view to impact positively on health outcomes later on.

Typically, behaviour change at this stage is influenced by peers rather than the family unit. Intervention in this age group is key in preventing chronic disease later in life as most health harming behaviours become habituated in adolescents and early adulthood. It is currently unclear from the above data how many adults locally are exposed to multiple risk factors, however these risk factors typically cluster and risk accumulates with additional risk factors.

Taking a life course approach to health behaviour, the WAY survey from 2015 showed that Wandsworth ranked 9th highest of all London Boroughs for 15-year-olds reporting three or more risky behaviours at 12.1% including smoking, alcohol use, drug use, physical inactivity. This was worse than the London average of 10.1% but lower than the England average of 15.9% 9.

Older adults and children are at an increased risk of the detrimental health impacts of poor health behavior. In Wandsworth, 9.8% of residents are aged over 65 years 10. There is predicted to be a 25% rise in 60-79-year-olds (from 33,986 in 2019 to 42,624 in 2029) and a 37% rise in 80+ year olds by 2029 (from 8,419 in 2019 to 11,511 in 2029), with the highest proportions of residents aged 80 and over in wards of St. Mary’s Park, East Putney, West Putney, Nightingale and Thamesfield12. In 2011 census, the largest number of those aged 65+ living alone was in West Putney (7.6%, n=785), Roehampton and Putney Heath (7.4%, n=770) and East Putney (7.1%, n=737).

Along with Age UK, The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has produced estimates of subjective loneliness for people aged 65 and over. Wandsworth ranks 13th highest of out 33 in London and 63rd highest out of 326 in England 11.

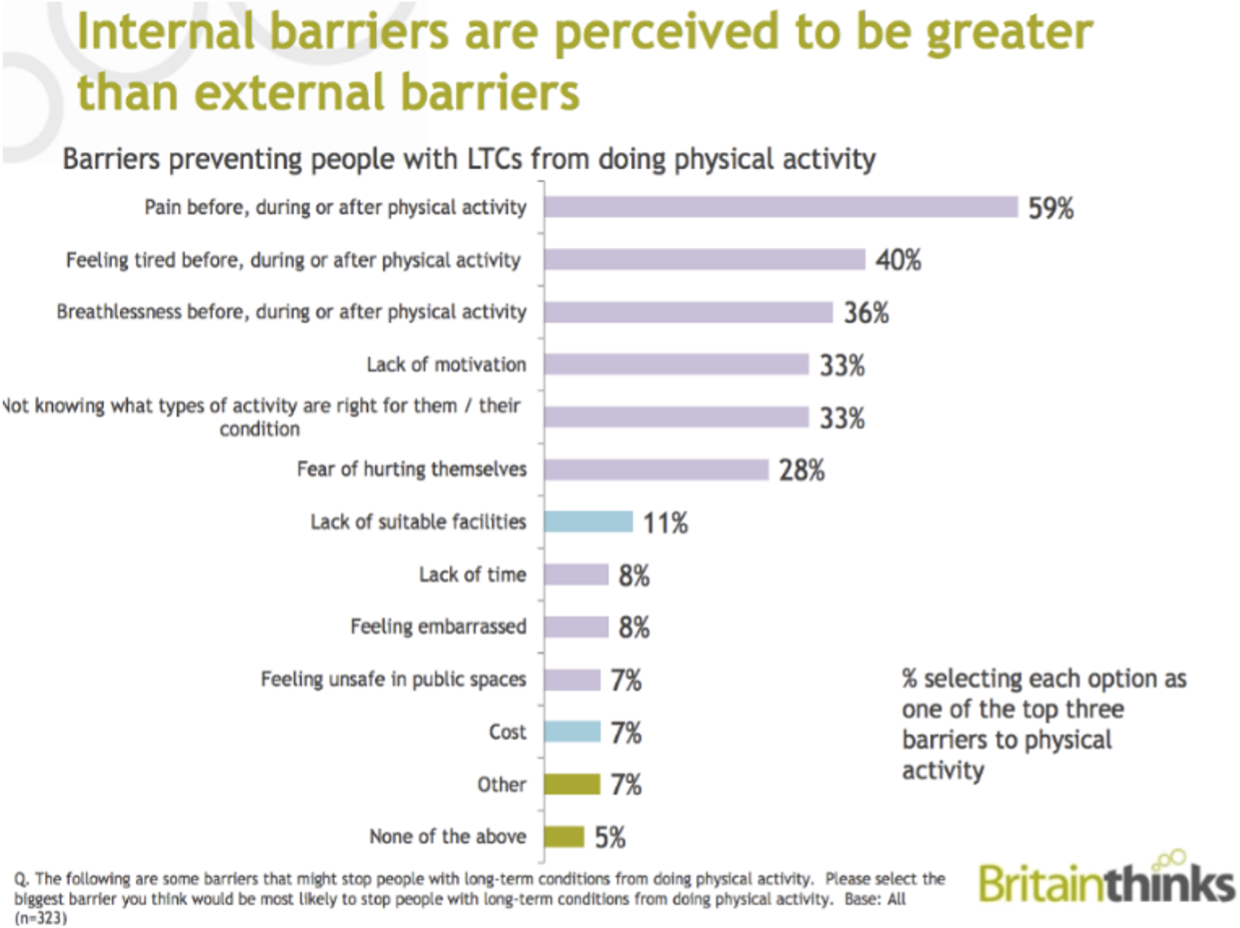

Towards the more severe end of poor health, we have long-term conditions. Long term conditions are associated with modifiable behaviours and develop over a prolonged period of time, offering preventative services time needed to arrange opportunities for intervention.

A place-based, community approach to design services to promote positive health behaviours in these areas, could reduce the risk of future ill-health, improve management of current long-term conditions, improve mental wellbeing and promote independence later in life, potentially increasing social connectivity.

1.2 Lifestyle Risk Factors for Long-term Conditions

Unhealthy behaviours tend to cluster together creating multiple risk factors for poor health both in individuals and communities. Chronic diseases are the leading causes of death and disability worldwide and the WHO acknowledges that rates of these conditions are accelerating globally and account for around 71% of deaths globally. The WHO states the 5 main risks for developing non-communicable disease risks are as follows, all of which involve modifiable human behaviours:

Unhealthy diet: high in salt, sugar or unhealthy fats

Tobacco use

Air pollution

Harmful use of alcohol

Physical inactivity

Cardiovascular disease, cancer, respiratory diseases and diabetes account for most of deaths globally, with the local information on each of these long-term conditions has been explored in separate sections of the JSNA. These longterm conditions are of course also the result of a combination of genetic, physiological, social and environmental factors alongside the modifiable individual behaviours. However, each of the conditions listed can, to some degree, be prevented, outcomes improved and in some cases disease processes reversed with changes in lifestyle behaviour.

These lifestyle behaviours can be introduced at an individual, community and societal level. Wandsworth health data may fare relatively well when compared to national data for certain lifestyle behaviours, however, this can be falsely reassuring when considering the multiple detrimental impacts of physical inactivity, poor diet or substance misuse can have on all aspects of health and wellbeing both the short and longer term.

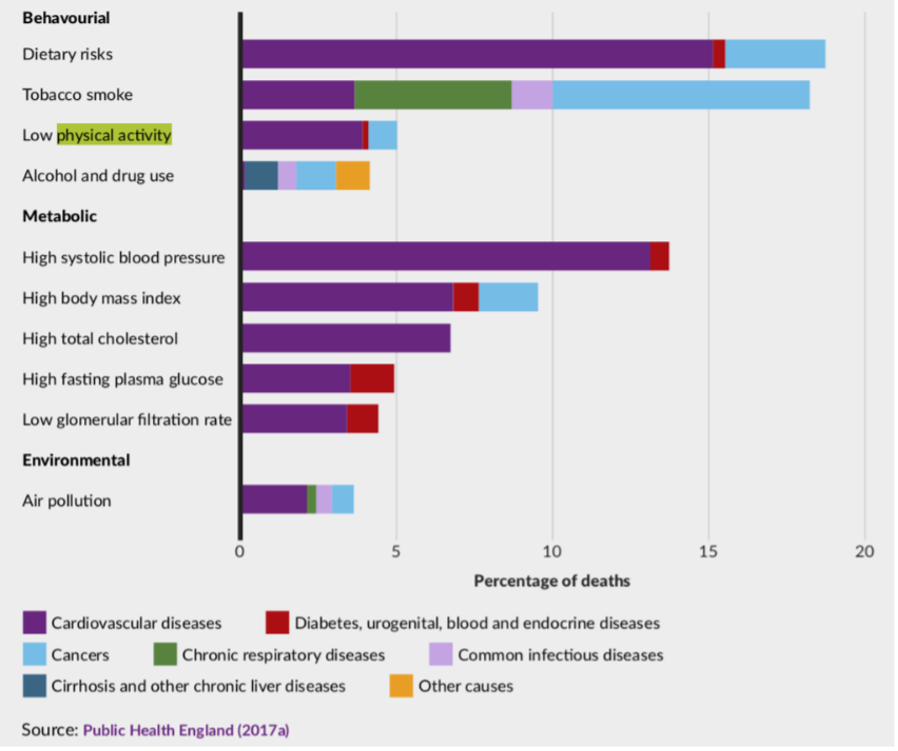

The relationship between risk factors and burden of disease is complex given the nature of the risks and interaction between behavioural, environmental, metabolic factors risk factor exposure. Depending on the disease considered, the degree of attributable risk varies, however, on the whole, the main risk factors accounting for the total burden of disease in England, according to PHE,14 15can be categorised into the following groups:

Behavioural Risks

Behavioural risks according to the Global Burden of Disease Study (2013) 12, 13.

- Tobacco use

- Alcohol consumption

- Drugs usage

- Diet low in fruits, vegetables or whole grains

- Physical inactivity

Prevalence and need locally:

Tobacco: Smoking prevalence for adults in Wandsworth is significantly lower than the London and England averages. In Wandsworth, there has been a substantial decrease in prevalence of smoking in adults between 2012 and 2022 (15.1% to 7.8%) comparative to London (18.2% to 11.7%) and England (19.3% to 12.7%) 14.

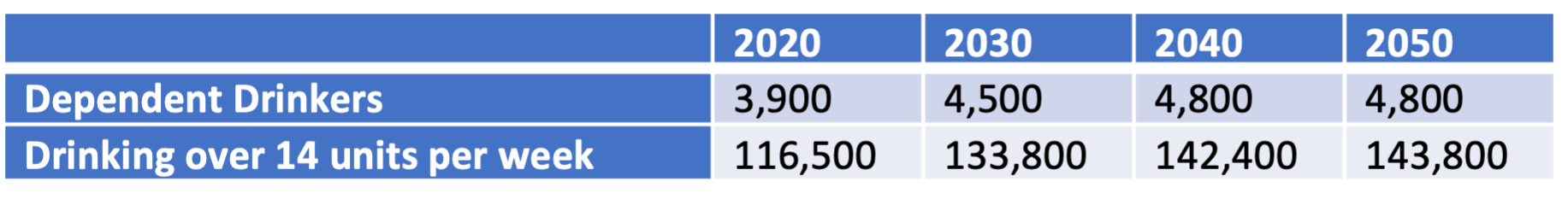

Alcohol: Between In 2014/15, 1.5% of Wandsworth residents are estimated to be dependent on alcohol - the 12th highest proportion in London 15.

Drugs: South West London had the highest proportion (11.7%) of drug use amongst all London regions as of 2018/1920. Further information can be found in the Wandsworth Substance Misuse Strategy 2020-2024.

Diet low in fruits, vegetables or whole grains: Based on the results from the Active Lives Survey, the proportion of the local population aged 16 and over who, when surveyed, reported that they had eaten the recommended 5 portions of fruit and vegetables on a usual day was 63.9% an increase from 57.8% in 2018/19 and significantly better than London (55.8%) and England (55.4%).

Physical inactivity: 15.8% of adults were reported to be physically inactive, completing less than 30 minutes of physical activity per week in 2021/22. While this is a lower proportion of the local population who are physically inactive than the London (22.9%) and England (22.3%) averages, the percentage of adults who are physically inactive locally has slightly increased from 15.7% in 2018/19.

Metabolic Risk Factors

Metabolic risks according to the Global Burden of Disease Study (2013) 16, 17

High body mass index

High systolic blood pressure

High plasma fasting glucose

Level of Need Locally:

High BMI: As of 2021/22 around half of adults aged 18+ (50.8%) in Wandsworth are still classified as overweight or obese, a small reduction from 52.9% in 2015/16. Whilst locally, obesity rates are lower than in London (55.9%) and England (63.8%), this data can seem falsely reassuring given that still half of the adult population in Wandsworth are at significant risk of morbidity and mortality associated with overweight and obesity 18.

High systolic blood pressure: In Wandsworth QOF data from 2021/22 recorded that 8.3% of patients on practice disease registers had a diagnosis of hypertension, which was a lower percentage of total patients than in London (11% - latest published figure for 2019/20) and England (14%) 19. However, Wandsworth identifies only 67% of the patients with hypertension, which is the 9th lowest proportion of diagnosed hypertension among London boroughs 20.

High plasma fasting glucose: 15,670 residents in Wandsworth were recorded as diabetic on practice disease registers in 2021/22, which was significantly lower than the London and England averages. However, the estimated diabetes diagnosis rate in 2018 was 60.9% which was lower compared to London (81.4% and England (78.0%). In 2015 the estimated prevalence of non-diabetic hyperglycaemia based on the characteristics of the local population in Wandsworth estimated a further 23,500 residents had non-diabetic hyperglycaemia, a metabolic risk factor 21.

Air Pollution

Around half of London’s air pollution is caused by road transport 22, toxic fumes from vehicles cause thousands of premature deaths every year and lead to young Londoners growing up with respiratory complications such as reduced lung volume and asthma. Key pollutants include NOx, PM10, PM2.5 and CO2. The largest sources of pollution locally were road transport, construction, and industrial and domestic health and power.

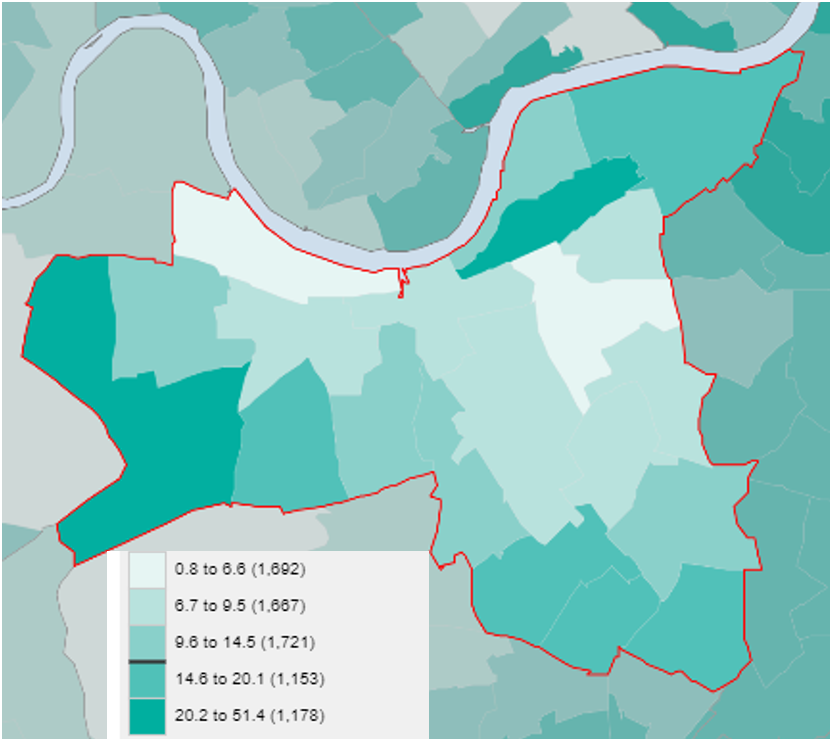

Wandsworth is home to seven Air Quality Network pollution analysers: Battersea, Lavender Hill, Putney, Putney High Street, Putney High Street Façade, Tooting High Street and Wandsworth Town Hall. In Wandsworth, between 2010 and 2016, The London Atmospheric Emissions Inventory estimated emissions of these key pollutants by source type. In their 2016 report they found that there were 800, 900 people in Wandsworth exposed to an annual average NO2 concentration that is above the Air Quality Strategy objective of 40µg/m3, based on the modelled 2016 ground level concentrations. This makes up 26% of the population, which is lower than inner London (48%) but much higher than outer London (3%) and higher than Greater London (24%). 23

Locally 6.6% of mortality in those aged 30+ from all causes can be attributed to air pollution. This is higher than the England average (5.5%) but similar to London (6.5%). Since 2010, the borough has seen a decrease in emission of CO2, NOx and other pollutants. The proportion of mortality in those aged 30+ from all causes that can be attributed to air pollination has fallen from 7.3% in 2010 to 6.6% in 2021.

More on air pollution can be found in JSNA Place chapter.

Trends in Risk Factor Exposure

Generally, over the last decade there are some notable trends in risk factor exposure in England 24:

- Declines in air pollution, smoking, cholesterol and hypertension

- Increases in exposure to low physical activity, high BMI and drug

use

- Little change in dietary exposures

In summary, in Wandsworth data suggests there has been:

- A decline in exposure to air pollution since 2010.

- There has been an increase in physical inactivity in adults locally, based on pre-COVID-19 data.

- Minimal changes have occurred in the proportion adults aged 18+ classed as overweight or obese or adults aged 18+ who are currently smoking.

- A large number of the residents are exposed to metabolic risks with around half of the adult population being classified as overweight or obese, 7.1% of residents are expected to have diabetes and 8.3% residents on practice lists with a diagnosis of hypertension.

- Inequalities exist in fruit and vegetable consumption between different groups in the borough.

It is currently unclear how many residents have multiple risk factors based on local data, however, based on national evidence, it would be expected that around 76,700 residents aged 15+ in Wandsworth are engaging in three or more behavioural risk factors. Therefore, a number of Wandsworth residents remain at risk from behavioural, metabolic and environmental risks associated poorer physical and mental health and wellbeing and subsequently, in the longer-term, chronic disease.

Addressing these risk factors and tackling health harming behaviours and their drivers in the borough will improve the health and wellbeing of residents, given we are aware of the cumulative nature of the above risks and the knowledge these risk factors tend to cluster.

1.3 Inequalities in Health Behaviours

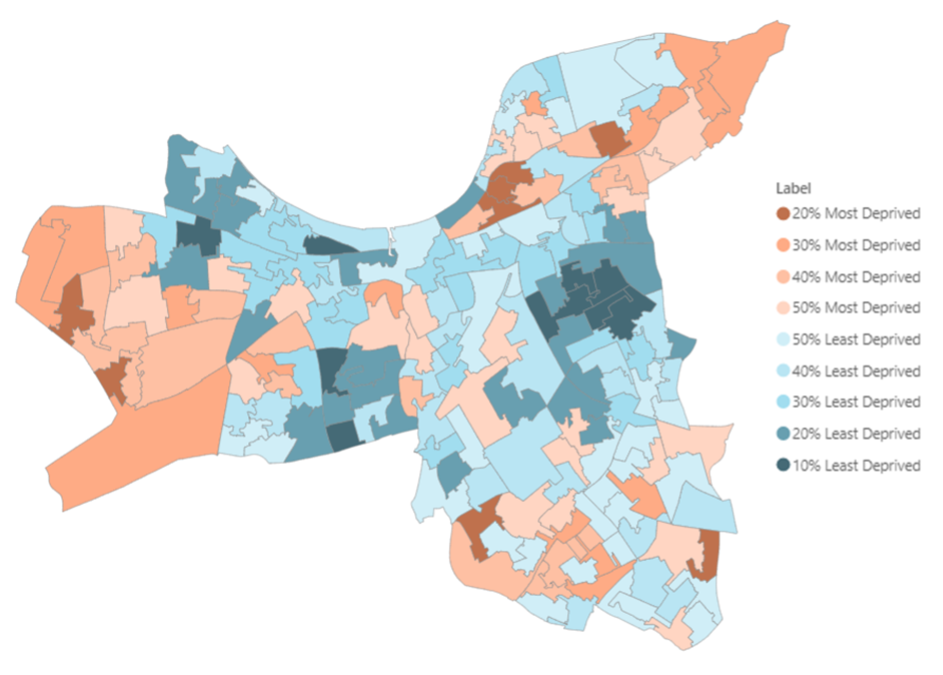

Health conditions are poorer in the top quintile of the most deprived areas in Wandsworth. 5.7% of people living in the most deprived areas of Wandsworth have bad or very bad health compared to 3.3% in all other areas of Wandsworth. In addition, 50% living in the most deprived areas consider themselves to have very good health. This is lower than the remaining population in Wandsworth (59.3%).

Often, clustering of behaviours detrimental to health is associated with social factors such as socio-economic status including educational attainment thus creating multiple risk factors for poor health. Individuals living in more deprived circumstances are more likely to be exposed to multiple risk factors, further influencing health behaviour and lifestyles which act to further widen social inequalities in health.

In 2019, the borough of Wandsworth ranked 173rd most deprived out of 317 local authorities across England: placing it within the 50% least deprived local authorities in England. The Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) estimates that Wandsworth residents working full-time earned £43,470 in 2019. This is amongst the top three annual earnings in London and England 35. However, there are income inequalities within the borough, that is how unequally income is distributed within the population; Wandsworth’s income inequality is the 6th highest in London 25

Overall in 2018, there were 68,853 people living in the most deprived areas of Wandsworth. These are small areas that fall into the top 20% of deprivation compared to the rest of Wandsworth. Of these people 13,903 are children and 8,874 are adults over 60.

There are in total, 27,822 people from ethnic and minority backgrounds living in the top 20% most deprived areas of Wandsworth. This makes up the largest proportion of people from ethnic and minority backgrounds compared to the other deprivation quintiles. This quintile has the lowest proportion of white ethnic groups (36,105), compared to the other quintiles for deprivation 26 27

The London Poverty Profile (2021) ranks London boroughs on key poverty and inequality indicators. In Wandsworth 11% of employed residents earn less than the London Living Wage - the joint lowest percentage in London, the poverty rate, that is the number of people that’s income falls below the poverty line is 22% of the population, this is below the London average (27%).

The average Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI) score for the borough indicates that 15% of children (0-15) are affected by income deprivation (2019), compared to 21% in 2015. Despite this and a relatively less deprived rank (150/317) compared to 2015 (123/326), Wandsworth remains within the 50% most deprived children local authorities nationally.

The average Income Deprivation Affecting Older People Index (IDAOPI) score indicates that 21% of older people (60+) are affected by income deprivation in Wandsworth, compared to 23% in 2015. However, the borough’s rank has not experienced notable change since 2015, retaining a position amongst the 8% most deprived LAs in England (26/317) 28

Given health behaviours begin to form in childhood and both older people and children are vulnerable to the increased risk of behaviours detrimental to health and that poor health behaviours are associated and exacerbated by socioeconomic status, addressing the wider determinants of health in children and older adults in Wandsworth is important.

The King’s Fund reported that individuals with no qualifications were more than five times as likely as those with higher education to engage in all four unhealthy behaviours including low physical inactivity, alcohol, smoking and poor diet. Wandsworth has one of the most educated populations with 66.5% have degree education or above, higher than England (36.8%), as of 2021. However, 1.4% of residents have no qualifications which is around 4,000 residents. While this is lower than England (6.5%), this accounts for 4,000 residents that are at higher risk of engaging in health harming behaviours than residents with higher education 29. Alongside this, the harm from certain unhealthy behaviours is likely to be higher in certain groups, therefore the risk of harm from the same exposure can disproportionately cause harm to certain groups within the community.

1.4 Impact of the Local Environment on Health Behaviours

Increasing physical activity, improving nutrition, getting the recommended amount of good quality sleep, spending time in nature and connecting with others fostering positive relationships and reducing stressors or improving ability to cope with stressors promotes a healthier lifestyle for physical and mental health. Positive health behaviours can prevent and improve management of and improve recovery from illness as well improving general health and wellbeing. Therefore, there is potential for multiple gains from engaging in healthy behaviours and interventions to improve the health behaviour of local residents can seek to address multiple health benefits.

Understanding the basis of human behaviour can help to inform local decision making around lifestyle services and behaviour change interventions to provide effective, high quality, compassionate services.

Humans’ instinctive behaviours and responses can, in current modern-day living, be detrimental to our health and wellbeing whereas historically, these same behaviours would have been advantageous for survival. In a relatively short time the environment we live in has changed to lend itself to an increasingly sedentary, convenient lifestyle with regular access to unhealthy foods, artificial ‘rewards’ and constant exposure to stressors. However, over the same timeframe, the systems within our bodies remained largely unchanged and have not adapted to our new conditions.

2. Smoking

2.1 Smoking Prevalence

Smoking Prevalence in adults (aged 18 and over) - current smokers (APS): In 2021 - 23, Wandsworth’s rate was 9.7%, which was the 6th lowest in London, 22.1% lower than the England average and 16.7% lower than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2021 - 23 was also 8.2% lower than in 2020 - 22, in comparison with 5.5% decrease in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Between 2017 - 19, 530 residents died from a smoking related death 30 and in 2019/20 there were 1,265 smoking related hospital admissions 31. In 2018-19, 112 women were smoking at time of delivery.

Smokers take more sick-leave from work than non-smokers.

Smoking increases the risk of disability and premature death.

£51,6m of potential wealth is lost from the local economy in Wandsworth each year due to smoking 32.

378 early deaths due to smoking result in 547 years of lost economic activity, costing businesses about £17.5m.

A further 118 employees in Wandsworth are economically inactive and unable to work due to smokingrelated sickness, resulting in an annual £5.7m. It is estimated that smoking breaks cost businesses in Wandsworth £20m 33.

Many current/former smokers require care in later life as a result of smoking-related illnesses. Each year these cost society in Wandsworth an additional £2.7m. There is a significant number of older people suffering from smoking attributable illnesses whose needs remain unmet by formal care. If all such individuals were instead to receive a formal social care, it would cost the system a potential further £61m 34.

It is estimated that the London Fire brigade will attend about 15 smoking-related house fires each year in Wandsworth. £2m is lost annually in the Borough as a result 35.

Smoking materials constitute 35% of all street litter. The majority of cigarette filters are non-biodegradable and must be collected and disposed in landfill sites. Smokers in Wandsworth consume about 244,010 cigarettes every day. Of these roughly 206,600 are filtered, resulting in among 35kg of waste daily. This represents 13 tonnes of waste annually, of which 5 tonnes is discarded as street litter that must be collected by the Council 36.

In Wandsworth, there are an estimated 246.1 smoking attributable deaths and 1154 potential years of life lost due to smoking related illness per 100,000 people. There are also 152.5 smoking attributable hospital admissions per 100,000 people in Wandsworth, which is less than the national average 37.

In Wandsworth there are 1,417 smoking attributable hospital admissions per 100,000. Smoking-related mortality for certain conditions are given as follows: COPD 51.0, CVD 20.0, lung cancer 53.2 (per 100,000 population) 38.

It is estimated that the annual cost of smoking in Wandsworth is £66.6m due to lost productivity (smoking breaks, sick days and early deaths), smoking related disease, social care costs, fires and passive smoking. Additional smoking related social care needs costs Wandsworth Borough Council £2.7 million per year, and local residents pay an additional £504,630 to self-fund their care 39.

As smoking prevalence increases with deprivation, the increased expenditure on smoking imposes a comparatively higher cost on proportionally more low-income households compared to high income households. Smoking rates are higher within certain groups and deprived communities and the rate of decline of smoking prevalence has not been equal among all populations. Targeting groups that are more likely to smoke is, therefore, one of the ways that services seek to reduce health inequalities.

Pregnancy

Smoking in pregnancy increases the risk of premature birth and neonatal complications, as well as miscarriage and still birth. Prevalence of smoking in pregnancy is considerably higher in more disadvantaged groups and in women under the age of 20 than in more affluent and older groups. There is, therefore, a major health inequality associated with smoking in pregnancy as disadvantaged groups are at a much greater risk of complications during and after pregnancy. Children who grow up with a parent who smokes are also more likely to be smokers themselves 40.

Smoking status at time of delivery: In 2024/25, Wandsworth’s rate was 3.9% (n=134), which was the 8th highest in London, 36.1% lower than the England average and 18.2% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2024/25 was also 11.3% lower than in 2010/11, in comparison with 55.3% decrease in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Young People

Discouraging young people from smoking is also a national priority. There are a number of factors associated with regular smoking amongst young people, including: having smokers at home. Many young people become addicted to tobacco before they fully understand the health risks and smoking rates amongst young people impacts on future adult smoking rates 41.

Deprivation

Smoking accounts for approximately half of the difference in life expectancy between the richest and the poorest in society 42. The prevalence of smoking increases with deprivation, as such, residents living in the 20% most deprived areas of the country are more likely to smoke than those in less deprived areas. A Government ambition is to reduce the inequality gap in smoking prevalence between those in routine and manual occupations and the general population. Smoking rates are almost three times higher among the lowest earners compared to the highest earners and smoking costs have the potential to push low-income households further below the poverty line.

Routine and Manual Workers

In England, around 1 in 4 (22.5%) people in routine and manual occupations smoked, this is around 2.5 times higher than people in managerial and professional occupations. In Wandsworth, routine and manual workers are more likely to smoke in relation to the England average (25.5% versus 22.5%).

Smoking prevalence in adults in routine and manual occupations (aged 18 to 64) - current smokers (APS): In 2023, Wandsworth’s rate was 6.6%, which was the 8th lowest in London, 66.0% lower than the England average and 56.4% lower than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2023 was also 78.9% lower than in 2011, in comparison with 39.2% decrease in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Mental Health Conditions

Smoking prevalence is also higher in people with mental health conditions. A report by the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Psychiatrists states that when compared to the general population, adults with a common mental health disorder (such as depression or anxiety) are twice as likely to smoke and adults with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder are three times more likely to smoke. High smoking rates among people with mental health problems are the single largest contributor to their 10 to 20-year reduced life expectancy compared to the rest of the population.

Smoking prevalence in adults (aged 18 and over) with serious mental illness (SMI): In 2014/15, Wandsworth’s rate was 38.4% (n=1252), which was the 16th lowest in London, 5.1% lower than the England average and 1.1% lower than the London average. Time series data were not available for this indicator.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Long-Term Conditions

Tobacco addiction causes and exacerbates Long Term Conditions (LTC). For example: People who smoke are much more likely to suffer from a LTC. Among those who are heavily addicted to tobacco, 44% self-report a long-term illness or disability compared with 32% of never smokers 55. People on low incomes are associated with higher rates of LTCs.

COPD caused 25,791 deaths in England in 2018 43. Smoking accounts for 86% of COPD related deaths. People with Asthma who smoke experience higher rates of hospitalisation, worse symptoms, and more rapid decline in lung function than those with asthma who do not smoke 44. Smoking significantly increases the risk of heart disease and stroke. People who smoke are 6 times more likely to have a stroke 45. People with diabetes who smoke have increased risks of complications and premature death 46.

Rates of smoking are also high among low-income groups thereby exacerbating LTCs and deepening health inequalities. Smoking is responsible for half the difference in life expectancy between the richest and poorest in society and, later in life, people who smoke are almost twice as likely to need some form of social care than never smokers 47.

The vision for the Wandsworth Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2015 – 2020 is to make Wandsworth the healthiest place to live in London by reducing the difference in health and life expectancy between the wealthiest and most deprived people.

2.2 Recent Developments to the Smoking Landscape

Nationally and locally the demand and uptake of smoking services has been affected by falling prevalence and the advent of e-cigarettes. Notably, within the last few years, new developments have been taking place at regional, sub-regional and locality levels that will influence the future direction of travel of stop smoking services. This has created a level of uncertainty regarding the emerging commissioning landscape and its impact on the provider markets.

There is a range of influences on future smoking prevalence, including the effect of e-cigarette use on smoking cessation, with new research suggesting that e-cigarettes have contributed to tens of thousands of additional quitters in England, thus accelerating the drop-in smoking rates across the country 48.

Public Health England (PHE) advise that vaping carries a small fraction of the risk of smoking. Using a nicotine-containing e-cigarette makes it much more likely that someone will quit successfully than relying on willpower alone – vaping is twice as effective for quitting smoking than NRT alone. But it is important to use UK-regulated e-liquids and never risk vaping home-made or illicit e-liquids.

Equally, it is important to address other forms of tobacco use, which are more common in certain communities. Shisha, which is one such use, creates smoke containing harmful chemicals, is becoming increasingly an area of concern. The populations where shisha is most commonly used, including BAME groups, are the same communities that are at higher risk of diseases such as heart attacks and stroke.

The health effects of Shisha smoking have received less research attention than cigarette smoking. However, the available evidence indicates that shisha smoking is associated with cancer, heart disease and lung disease. There have also been reports of increased risk of infectious disease, and the large amount of carbon monoxide created by the constant heating of tobacco by burning charcoal introduces the risk of carbon monoxide poisoning. The existing evidence base supports the need to monitor shisha smoking and minimise use, particularly regular use.

In recent decades, shisha has become more popular in western countries, particularly in young people. Despite a low prevalence of shisha use at the national level, additional data collected in specific communities highlight that shisha use is an issue of growing concern in certain areas. Local tobacco control programmes need to be sensitive to local cultural context 49.

Smokers take more sick-leave from work than non-smokers and smoking increase the risk of disability and premature death. £51,6m of potential wealth is lost from the local economy in Wandsworth each year due to smoking 50.

378 early deaths due to smoking result in 547 years of lost economic activity, costing businesses about £17.5m. A further 118 employees in Wandsworth are economically inactive and unable to work due to smoking-related sickness, resulting in an annual £5.7m. It is estimated that smoking breaks cost businesses in Wandsworth £20m 51.

Many current/former smokers require care in later life as a result of smoking-related illnesses. Each year this costs society in Wandsworth an additional £2.7m. There is a significant number of older people suffering from smoking attributable illnesses whose needs remain unmet by formal care. If all such individuals were instead to receive formal social care, it would cost the system a potential further £61m 52.

2.3 Stop Smoking Services

NICE recommends that services should aim to treat at least 5% of the estimated local population of people who smoke or use tobacco in any form each year. Of this figure, 35% are expected to be validated as 4-week quitters. Applying this figure to Wandsworth means that the annual target is 600 validated quits.

Smoking Cessation interventions are important in helping to improve people’s health, quality of life and life expectancy, as well as cut costs to healthcare and public services. In July 2017 the Government published the Tobacco Control Plan – Delivery Plan 2017-22 53. The plan identifies specific areas of focus including:

- Reduce the prevalence of 15-year olds who regularly smoke from 8% to 3% or less by the end of 2022

- Reduce smoking prevalence amongst adults in England from 15.5% to 12% or less by the end of 2022

- Reduce the inequality gap in smoking prevalence between those in routine and manual occupations and the general population by the end of 2022

- Reduce the prevalence of smoking in pregnancy to 6% or less by the end of 2022

Data relating to the local stop smoking service is provided through the data management system – Quit Manager. This data is used to determine quit figures for the borough, which are reported to the Department of Health (DoH) for inclusion within the national datasets. The Council is reliant on publicly available information, much of which has gaps in data and/or limitations in what is reported, particularly at a local level. For example, it is not currently possible to compare smoking prevalence rates at 15 years in Wandsworth to the region or England. Improved reporting of data and increased granularity in reported data would support work to increase targeting to most at risk populations and groups more likely to smoke.

The Wandsworth Business Plan emphasises the importance of investing in good local services that protect the most vulnerable. Key relatable actions include:

- Helping people get on in life

- Encouraging people to live health, fulfilled and independent lives

Two-thirds of smokers say they want to quit, however most try to do so unaided, which is the least effective method. Smokers who get the right support are up to four times as likely to quit successfully 54.

Wandsworth Council operates a successful smoking cessation service. The service is delivered in collaboration with primary care (GP surgeries and pharmacies), NHS trusts, voluntary organisations and outreach with local community venues. The Council also has a team of smoking cessation sessional workers who support delivery in stop smoking interventions across all settings. Service users are supported with access to free Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) for up to 6 weeks. The Council funds NRT provided through community pharmacists.

Wandsworth Council is also part of the London Smoking Cessation Transformation Programme (LSCTP). The LSCTP vision is to change smoking behaviours and encourage more quit attempts among the general population to support London to become the first smoke free city in England by 2029. Stop Smoking London is the public facing identity of the LSCTP 55. Stop Smoking London offers telephone consultations for people who do not need face-to-face interventions or who are time-poor.

During 2018-19, Wandsworth Council supported 690 people to successfully stop smoking.

Young People

The Council works with Catch 22 56 to provide smoking cessation advice and treatment at schools and colleges. Catch 22 is a social business specialising in early intervention, and targeted support services including substance misuse to young people. Catch 22 also conducts outreach and provides workshops to educate young people about the risks associated with smoking and offers stop smoking support to smokers who want to quit.

In 2018/19 182 young people (12-18) assessed support to quit smoking. Of these, 115 were aged between 12-15, and 93 went on to quit smoking successfully.

Adults

Wandsworth Councils Stop Smoking Service 57 offers free help, advise and access to stop smoking medications to all adult smokers who live, Work or are receiving long-term treatment in the Wandsworth area.

Service provision includes: • Tips on managing withdrawal symptoms and coping with smoking triggers • Regular carbon monoxide checks • Accurate information on what to expect when trying to quit and how to deal with difficult situations • Access to stop smoking medications and guidance on using these • Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) • Advise on professional help offered by GPs and pharmacists in the Borough

There are well established drop-in services at St Georges and Queen Mary’s Hospital”. These drop-in services work closely with the Hospital stop smoking leads to support in-patients, out-patients and maternity patients who require support to quit smoking. The service also supports people going into surgery that need to stop before their procedure:

- Patients who are being discharged and may need further smoking cessation support can also access these drop-in services

- Stop Smoking support is also being accessed through mental health settings through Stop Smoking Wards and Grounds Project with the mental health trust. Staff have been trained and specialist advisors have been provided to support the effective delivery of smoking cessation support at all levels.

Smoking Quitters

The effectiveness of the local sFIndmoking cessation services is measured using the proportion of smoking quitters at 4 weeks out of the estimated local smokers’ population. Successful quitters are those smokers who successfully quit at the four-week follow-up. A client is counted as a ‘self-reported 4-week quitter’ when assessed four weeks after the designated quit date, if they declare that they have not smoked, even a single puff on a cigarette, in the past two weeks.

Proportion of local smoking population who successfully quit smoking: In 2023/24, Wandsworth’s rate was 1.2% (n=312), which was the 16th highest in London, 35.1% lower than the England average and 30.1% lower than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2023/24 was also 68.3% lower than in 2013/14, in comparison with 52.4% decrease in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Smokers that have successfully quit at 4 weeks (CO validated): In 2022/23, Wandsworth’s rate was 208.6 per 100,000 smokers aged 16+ (n=45), which was the 9th highest in London, 12.0% lower than the England average and 16.3% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2022/23 was also 92.7% lower than in 2013/14, in comparison with 91.0% decrease in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Cost per smoking quitter: In 2022/23, Wandsworth’s rate was 318.0 £ (n=110455), which was the 8th lowest in London, 47.6% lower than the England average and 48.1% lower than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2022/23 was also 6.1% higher than in 2013/14, in comparison with 114.1% increase in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

2.5 Evidence Based Interventions/Approaches

According to NICE, commissioners and providers of stop smoking services should implement the following approaches locally:

Use sustainability and transformation plans, health and wellbeing strategies, and any other relevant local strategies and plans to ensure evidence-based stop smoking interventions and services are available for everyone who smokes

Use Public Health England’s public health profiles to estimate smoking prevalence among the local population

Prioritise specific groups who are at high risk of tobacco-related harm. These may include:

People with mental health problems, including mental health disorders (for example, see NICE’s guidelines on depression in adults and smoking: acute, maternity and mental health services) and smoking: acute, maternity and mental health services)

People who misuse substances (for example, see NICE’s guideline on coexisting severe mental illness and substance misuse: community health and social care services)

People with health conditions caused or made worse by smoking (for example, see NICE’s guidelines on cardiovascular disease: identifying and supporting people most at risk of dying early, type 1 diabetes in adults, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)

People with a smoking-related illness (see NICE’s guideline on lung cancer)

Populations with a high prevalence of smoking-related morbidity or a particularly high susceptibility to harm

Communities or groups with particularly high smoking prevalence (such as manual workers, travellers, and lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans people)

People in custodial settings

People living in disadvantaged circumstances

Pregnant women who smoke (see NICE’s guideline on smoking: stopping in pregnancy and after childbirth).

In addition, NICE have produced a series of evidence-based recommendations for commissioners and providers of Smoking Cessation Services, which include the following:

Ensure the following evidence-based interventions are available for adults who smoke:

- Behavioural support (individual and group)

- Bupropion

- Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) – short and long acting

- Varenicline

- Very brief advice

Consider text messaging as an adjunct to behavioural support

Offer Varenicline as an option for adults who want to stop smoking, normally only as part of a programme of behavioural support, in line with NICE’s technology appraisal guidance on varenicline

For adults, prescribe or provide varenicline, bupropion or NRT before they stop smoking

Agree a quit date set within the first 2 weeks of bupropion treatment and within the first 1 to 2 weeks of Varenicline treatment. Reassess the person shortly before the prescription ends

Agree a quit date if NRT is prescribed. Ensure that the person has NRT ready to start the day before the quit date

Consider NRT for young people over 12 who are smoking and dependent on nicotine. If this is prescribed, offer it with behavioural support

Ensure behavioural support is provided by trained stop smoking staff (see the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT) training standard

3. Healthy Eating

3.1 Healthy Eating Definition

A healthy, balanced diet is vital to enable optimal health and wellbeing. In eating a wide variety of foods in the right proportions, we ensure enough intake of the nutrients essential for health. Forming part of healthy eating, good nutrition is not simply defined as following a diet which is low in fat, salt and sugar, rather it is eating a wide range of nourishing foods to enable the body to function well and help to protect against disease. This includes eating essential vitamins and minerals, as well as an appropriate energy (calorie) and macronutrients (fat, protein and carbohydrate) intake.

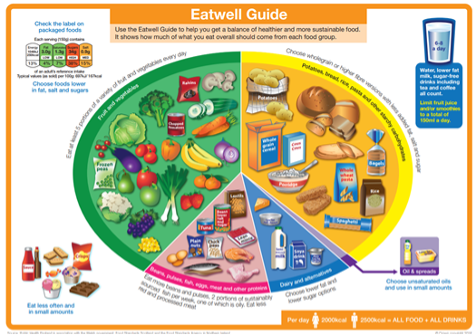

Consuming a healthy diet throughout the life course helps to prevent health problems caused by poor diet, as well as a range of non-communicable diseases and conditions. Current nutrition guidance from Public Health England (PHE) and the NHS, recommends that balance is the key to a healthy diet. Eating a variety of foods in the right proportions and consuming a suitable amount of food and drink during the differing life stages, will achieve and maintain a healthy body weight and help prevent diet-related health conditions.

Expert evidence-based scientific research forming these guidelines, promotes a diet based on starchy carbohydrate foods such as potatoes, wholegrain bread, rice and pasta; plenty of fruit and vegetables (recommendation is at least five portions a day); protein-rich foods such as meat, fish, tofu and lentils; milk and dairy foods; and limited fat, salt and sugar. By following these recommendations, intake of dietary fibre and ‘free’ sugars along national regulations will be easier to achieve; currently these two food groups are under and over consumed respectively across the general population.

The PHE ‘Eatwell Guide’ 59 presented in Figure 28 highlights the different types of food that make up our diet and illustrates the proportions that should be eaten to achieve the recommendations.

3.2 Healthy Eating and Nutrition

Poor diet is a public health issue as it increases the risk of some cancers and cardiovascular disease (CVD), both of which are major causes of premature death. Dietary risks, such as low fruit and vegetable intake and obesity contributes to approximately one third of all deaths from cancer and CVD 60. These diseases, along with type 2 diabetes (T2D), which increases CVD risk, are associated with obesity, which has a very high prevalence in adults in London and England 61. Alongside obesity, it is important not to forget the impact of malnutrition; under-eating, not having enough protein, vitamin rich foods and dehydration can also cause health problems, particularly amongst the young 62 and elderly 63.

According to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), healthier diets could prevent around 1 in 20 cancers [URL: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/causes-of-cancer/diet-and-cancer]. Regularly eating foods high in fibre can reduce the risk of some cancers and over consumption of processed and red meat, and alcohol can increase the risk of some cancers. Furthermore, controlling intake of salt, saturated fats and transfats can reduce the risk of CVD 64. CVD is often caused by high blood pressure and high cholesterol, which can potentially be reduced without the need for medication by following a healthy diet and exercise plan.

The impact of good nutrition on brain health can also not be dismissed. Malnutrition affects both mental and physical wellbeing. Eating a nutrient-rich diet, particularly one that has lots of fruits and vegetables, omega 3 fats, and low amounts of sodium and saturated fats, helps to maintain good brain health, which is important for the prevention of dementia 65, coronary heart disease, high blood pressure and high cholesterol; all these conditions can also be alleviated, to some extent, by following a healthy diet. Promoting optimal nutrition for all Wandsworth residents is important to prevent the onset of these long-term conditions.

The way we shop, cook and eat food has changed significantly over the last decade, particularly with the availability and affordability, of fast food and eating out. The increased production of processed food, rapid urbanisation and changing lifestyles has led to a shift in dietary patterns. People are now consuming more ‘ultra-processed’ foods, which are high in energy, saturated fats, free sugars and salt/sodium. Consequently, a significant proportion of the population are not consuming adequate intakes of fruit, vegetables and dietary fibre 66. The number of takeaways in London alone has increased from 4,100 in 2010 to 5,335 in 2018 . The introduction of smart phone apps has made it even easier to have fast food delivered to home or work and this market has increased by 72% in the last decade 67.

The food market has shown some positive steps towards healthy eating. For example, there are several companies offering households to subscribe to fruit and vegetable boxes or for deliveries of fresh ingredients to enable them to cook from scratch with pre-prepared ingredients delivered to homes and this represents a positive step towards healthy eating at home. However, this approach tends to serve those who have the financial resources and there remains population groups who face attitudinal, financial or knowledge barriers to benefit from healthy eating.

The issue of being overweight or obese is usually given most attention when healthy or unhealthy eating is being discussed. However, it is important to consider the other less visible effects of unhealthy eating and poor nutrition; the risk this poses to health and the groups who may be most affected. For example, a diet with high salt intake or low vitamin consumption may not cause weight gain but can still put an individual’s health at risk.

Sustainability and waste are also an issue associated with food. It is estimated that food and drink accounts for 10% of London’s total consumption-based greenhouse gas emissions. For every two tonnes of food eaten in the UK, another tonne is wasted 68. Climate change impacts on fuel and food prices, which further impact on population groups that are already disadvantaged or vulnerable.

Healthy Behaviours

Current UK diet and nutrition recommendations include 69:

- At least 5 portions of fruit and vegetables per day for those aged 11 years and over.

- For adults (ages 19 and over), average intakes of red and processed meat should not exceed 70 grams per day * At least 1 portion of oily fish (140 grams) per week for all ages (equivalent to 20 grams per day).

- Limit free sugars to no more than 5% of daily calorie intake.

- Limit saturated fat intake to no more than 11% of daily calorie intake.

National trends in diets indicate that the general population may not be consuming the right foods to support a healthy lifestyle:

- Ready meals and convenience meat products continue a clear upward purchasing trend.

- Purchases of fish and fish products are falling steadily.

- Fresh green vegetables have shown slight downward trend, however, there has been a 5 % increase in purchase of other fresh vegetables.

- Potato purchases continue a downward trend.

- Purchases of both white and wholemeal bread have fallen.

- Milk purchases have generally declined over the last 10 years.

- Between 2013 and 2016/17, purchases of takeaway food brought home have increased by 10%. Expenditure on takeaway foods was £2.17 per person per week in 2016/17, 23% higher than in 2013.

3.4 Dietary Behaviours in Wandsworth

In Wandsworth, the proportion of adults meeting the recommended ‘5 a day’ on a usual day is broadly similar to the London and England average (58% vs 55%). In Wandsworth, 44% adults are reported to drink more than the recommended units of alcohol a week, which is the highest in London and well above the London average (26%).

Whilst there is no local data available about the diets of Wandsworth residents, the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) provides an indicator that adults may not be consuming the right foods to support a healthy lifestyle 80:

- The average daily intake of ‘free’ sugars (those added to food or drinks, or found naturally in honey, syrups and unsweetened fruit juices) is 11%, which is double the recommended daily intake of no more than 5%. Main sources of free sugars in all age groups are biscuits, buns, cakes and pastries; sugar, preserves and confectionery; cereal and cereal products; sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs) (including fruit juice), and for adult men, beer, lager and cider are also contributors 81.

- Only 9% of 19-64-year-olds and 7% of those aged 65 and above are meeting the recommended daily intake of fibre of 30g per day 82. Main sources of fibre include wholegrains (for example, brown pasta, breads and oats), vegetables and fruit (including their skins and peel)

- Average weekly consumption of oily fish is 77g which is around half the recommended amount (140g). Oily fish includes anchovies, carp, trout, mackerel, herring, pilchards, salmon (including canned), sardines, sprats, swordfish, tuna (fresh only)

3.5 The Obesogenic Environment

In recent years Britain has become a nation where being overweight is prevalent; by 2050, around 50% of adults and 25% of all children under 16 could be obese 86.

Today’s ‘obesogenic’ environment, with its abundance of convenience and energy dense foods and increased sedentary lifestyles, reducing the prevalence of obesity is challenging. Exposure to fast food through advertising is known to influence the purchase and consumption of food and forms part of the issue that need addressing around the obesogenic environment. Locally, Public Health carried out a snapshot of fast-food adverts in Wandsworth and found that of the adverts advertising food products, the vast majority were for foods high in fat, salt and sugar.

A report published in 2018 by Cancer Research UK found young people who recalled seeing junk food adverts were more than twice as likely to be obese. The same study identified 87% of young people found adverts for high fat, salt and sugar products appealing, with three quarters tempted to eat a product after seeing such an advert. The purpose of the ban is to reduce this exposure to foods and drinks high in fat, salt and sugar and therefore reduce the likelihood of those foods being purchased and consumed.

3.6 Limitations to the Data/Information

Additional data would assist with building a more comprehensive picture locally about diet and nutrition. For example, the following health related behaviour measures relating to food and drink would be useful at a Borough level:

- Local data on fast food consumption and takeaway usage

- Local data based on diet and nutrition survey measures

- Local barriers to following a healthy diet

- Level of skills and education levels amongst adults around preparing nutritious meals

- Data on fizzy drink consumption

- Data on felt need/perceived need in relation to healthy eating

- Data from adults with learning disability about healthy eating

3.7 Current Services

The Council offers both public facing services and policy approaches to support healthy eating for adults in particular groups. These are as follows:

- Men’s Weight Management Programme Guys Get Active - In partnership with Wandsworth Council, Enable Leisure and Culture are relaunching a programme to help local men lose weight. Adapted to suit the current climate, Guys Get Active incorporates weekly physical activity and nutrition sessions delivered face to face as well as virtually. The programme is focused on creating peer to peer support between men who want to lose weight and improve their health. Led by qualified professionals who can adapt the exercises to suit individual needs, Guys Get Active is perfect for all abilities and fitness levels. These sessions are exclusively for men who live, work or are registered with a GP in the Wandsworth Borough with a BMI of 27.5+ or a diagnosis on type 2 diabetes, and a willingness to lose weight

- Wandsworth offers residents an Adult Weight Management Programme which offers vouchers for 12 weeks membership to either Slimming World or Weight Watchers. The vouchers are offered through GP or self-referral

- Including healthy catering criteria in Commissioned Service Contracts, for example Age Well Centres and Leisure Centres. Plans are being developed to influence the food environment by reducing exposure to unhealthy food through retail planning, healthy catering for restaurants and takeaways. The council is also considering the feasibility of limiting exposure to high fat salt sugar foods through advertising and marketing restrictions

- Including healthy eating criteria in the Quality Assurance Process in contracted supported living providers with a contract in Wandsworth

The Voluntary Sector also provides a number of services and projects for Wandsworth residents to help them and their families to eat healthily, particularly those who are low income or in need of emergency support. For example, Wandsworth Foodbank, Wandsworth Food Partnership and Waste Not Want Not, a food sharing and food sourcing scheme in Battersea. Age UK also offer support for older people such as the Man With A Pan cooking initiative for older men who live alone.

3.8 Evidence Based Interventions/Approaches

Evidence Based Marketing and Campaigns

PHE and the NHS deliver two key marketing campaigns to support healthy eating amongst adults One You and One You: Nutrition on the Go to support eating out 87

There is also the Sugar Smart campaign which is delivered by Sustain and supported by PHE 88. This campaign has been adopted by other Boroughs across London and England.

NICE Guidance and Quality Standards

There is a wide range of NICE guidance on healthy eating and nutrition, which recommends evidence-based interventions. Also cited here are NICE Guidance and Quality Standards for the prevention obesity and excess weight gain and type 2 diabetes:

- Preventing excess weight gain (NG7)

- Obesity prevention (CG43)

- Weight management: lifestyle services for overweight or obese adults (PH53)

- Weight management before, during and after pregnancy (PH27)

- Cardiovascular disease prevention (PH25)

- Promoting health and preventing premature mortality in black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups (QS167)

- Obesity in adults: prevention and lifestyle weight management programmes (QS111)

- Obesity: working with local communities (PH42)

- Type 2 diabetes prevention: population and community-level interventions (PH35)

- Dementia, disability and frailty in later life - mid-life approaches to delay or prevent (NG16)

4. Physical Activity

Physical Activity (PA) is universally acknowledged to be an important part of healthy functioning and well-being. An active lifestyle is essential for health and the health benefits of routine PA and exercise 89 participation is irrefutable. PA reduces the risk of many preventable diseases, from cancer to diabetes, and conditions like obesity and depression 90. PA increases your chances of staying independent in later life, thereby reducing demand for NHS an Adult Social Care services.

National Picture of Physical Activity

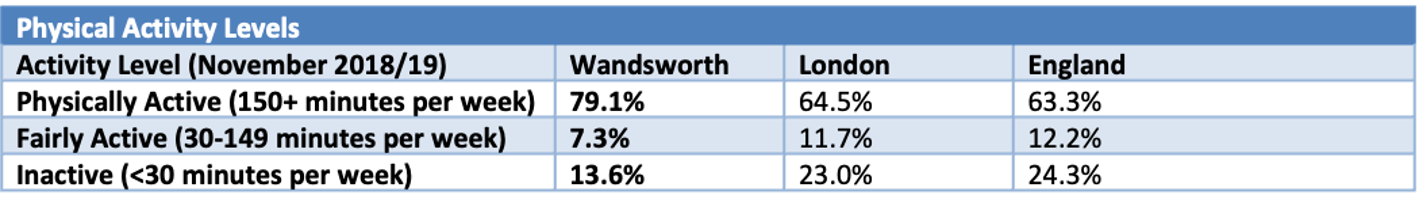

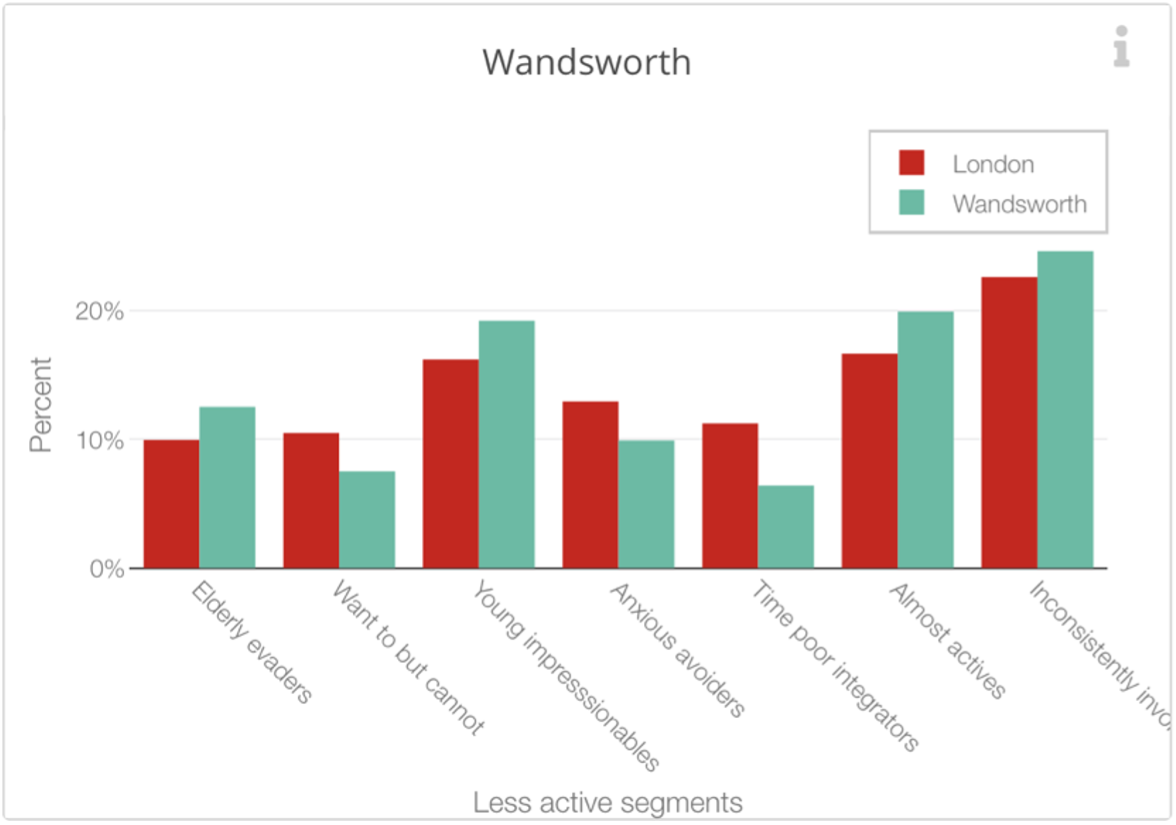

The national picture shows that over the last 50 years, the UK has experienced a 20% decline in PA levels (UK Active, 2014). It also shows that around 1 in 3 or 34% of men and 1 in 2 or 42% of women are not active enough for good health 91. The good news is that Wandsworth has over the past few years countered that trend. Wandsworth is currently way ahead of both the London and England average with circa 79% of residents (estimate of circa 211,60) self-reporting being physically activate and 13.6% as being inactive (circa 36,500 people aged 20 years or more) in the Active Lives Survey (November 2018/19)92, pre-pandemic. During the pandemic inactivity levels rose at the expense of people reporting being active or ‘fairly active’ 93 but these were considered not significant changes by Active lives Survey report. The latest figures (period May 2020/21) are 73.3% active (150+ mins) and those who are inactive has increased to 17.9% (circa 48,400 residents) 94. Regarding the latter that represents and additional circa 11,900 inactive people compared to almost 2-years ago.

The UK has experienced a 20% decline in PA levels (UK Active, 2014) to date. PHE estimates that if this trend continues, without any preventive measures, the number of people who are less active will increase to 35% of the UK population by 2030.

Wandsworth’s total population is circa 328,828 residents and is due to grow to circa 373,000 by 2029. The number of adults aged 18 years and over is circa 267,600 or from 20 years and above c.258,762 (second largest in Inner London). Wandsworth population is characterised by a higher percentage of people aged 26-34, a highly educated population, higher than average employment rates. The data we have on PA and inactivity is not broken down by age, nor do we have Wandsworth data by gender, ethnicity nor locality.

Declining Trend in Physical Activity

Over the last 50 years, the UK has experienced a 20% decline in PA levels (UK Active, 2014). If current trends continue unchallenged then it is estimated that 35% of people would become less active by 2030 . If applied to Wandsworth we would see the number of inactive people grow, based on May 2018/19 figures, from circa 13.6% (36,500 people aged 20 years or more) to circa 22.8% (54,618 people aged 30 years or more) by 2029. Sport England’s latest Active Lives Survey found that a quarter of adults (11.3 million) do less than thirty minutes of activity per week in the UK

The Active Wandsworth Strategy

The Active Wandsworth Strategy 2017-2021 has four key themes with several key outcomes and associated objectives. These all help to increase PA as part of a holistic approach, addressing both individual factors Such as psychology, food consumption, physical activity and biology as well as societal influences (this includes changes in the range, marketing, price and accessibility of energy-dense foods, which make it ‘harder to avoid’ obesity (King’s Fund), active travel, use of green spaces, etc ), to improve residents’ health and well-being. This approach also seeks to scale up professional to community-led initiatives that will make people more active.

The Active Wandsworth Strategy is due to be renewed in 2022/23 for the next 5-years. This JSNA will support and inform that process.

4.1 Physical Activity Guidelines

Both OHID and the UK Chief Medical Officer (CMO) have produced PA Guidelines, that cover older people, pregnancy and disability. These are summarised below.

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID)

Tackling physical inactivity is critical to delivering many national priorities e.g., reducing Dementia and Obesity rates and giving every child the best start in life.

Being physically active is define as doing at least 15 moderate intensity equivalent (MIE) minutes of PA per week 95 or more in the previous 28 days. Alternatively, this can be achieved by 75 minute of vigorous intensity activity a week or more. Physically inactivity is defined as doing less than 30 MIE minutes of PA per week. For adults not reaching 150mins the guidance also says doing ‘more’ will always be beneficial. But the most benefits are achieved at 150 MIE.

Being physically active is define as doing at least 15 moderate intensity equivalent (MIE) minutes of PA per week or more in the previous 28 days. Alternatively, this can be achieved by 75 minute of vigorous intensity activity a week or more. Physically inactivity is defined as doing less than 30 MIE minutes of PA per week.

OHID guidance also states that a well a being physically active, all adults are advised to minimise the time spent being sedentary for extended period. Even among individuals who are active at the recommended levels, spending large amounts of time being sedentary increases the risk of adverse health outcomes, see Health matters: getting every adult active every day.

UK Chief Medical Officer

Adults and older people should:

- Do at least 150 minutes (moderate intensity) or 75 minutes (vigorous activity) or a combination of moderate and vigorous PA per week, nonetheless some exercise is good, more is better

- Include strength and balance activities two days per week

- Older adults at risk of falls should also incorporate balance and coordination PA at least two days per week

- Minimise sedentary behaviours

World Health Organisation

The term PA should not be confused with exercise which is a subcategory of PA which is planned, structured, repetitive and aims to improve or maintain one or more components of physical fitness. Beyond exercise, any other PA that is done during leisure time, for transport to get to and from place, or as part of a person’s work, has health benefits.

The most recent updated guidelines also include advice on safe levels of activity for pregnant and postpartum women as well as older people.

4.2 Impact and Benefits of Physical Activity

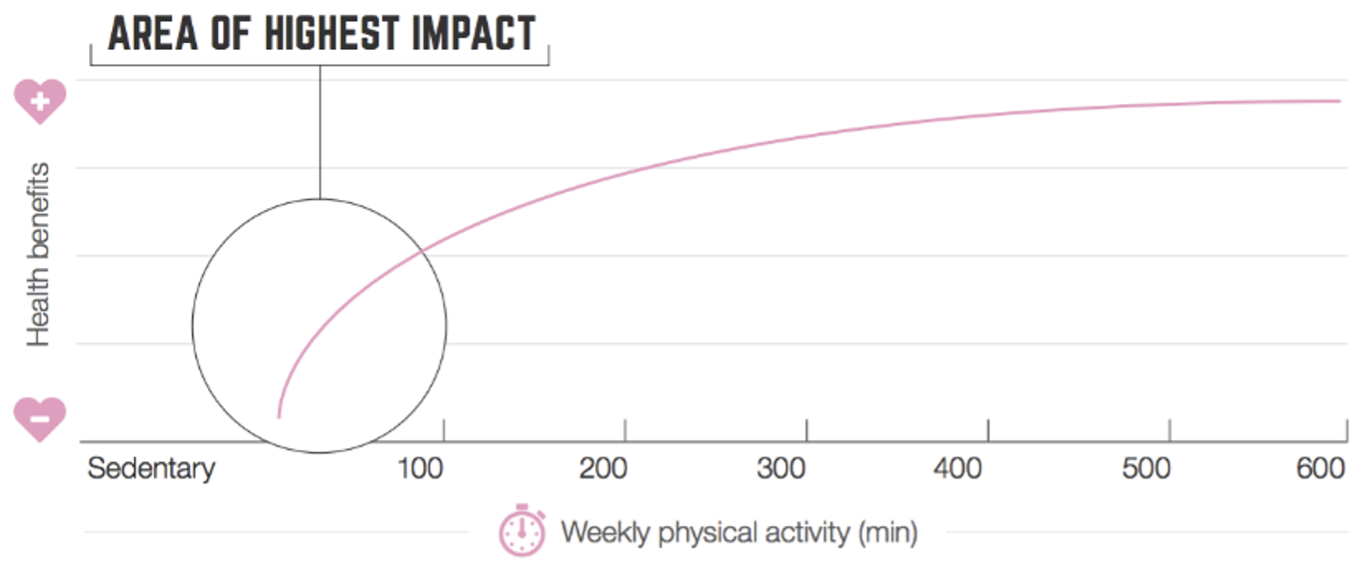

Being active is also good for adults, children and old alike. Prevention has become increasingly important in recent years, as the cornerstone of the drive to improve peoples’ health and well-being as well as their quality of life. PA helps reduce peoples’ need for high-cost health treatments and care services. Therefore, prevention is now seen as everyone’s business and PA remains one of the core elements of a healthier lifestyle. PA also helps us get out our homes and connect with others, avoiding social isolation. It also helps mitigate against substantial economic burden 96, as well as increasing social capital and community spirit.

The importance of being physically active and not having sedentary lifestyles is championed by CMOs. They advocate that the strength of the relationship between PA and health outcomes persists throughout people’s lives, highlighting the potential health gains that could be achieved if more people become more active throughout the life-course 97.

This ties into the Council’s public health prevention focus on Start Well, Live Well and Age Well in this JSNA. Regarding the latter the evidence according to CMO is that:

- Regular PA contributes to the key determinants of healthy ageing: good physical and mental function; opportunities for social interaction; a sense of control over, responsibility for one’s own health and well-being; and managing or coping with disease symptoms and functional limitations.

- Increasing PA contributes to improving social functioning and reducing loneliness and social isolation, especially as you age

- PA contributes to increased physical function, reduced impairment, independent living, and improved quality of life in both healthy and frail older adults

- PA in later life can help treat and offset the symptoms of a range of chronic conditions (e.g., Depression, CVD, Parkinson’s Disease)

- New evidence, [specifically for older people] has strengthened and reinforced the main elements of those

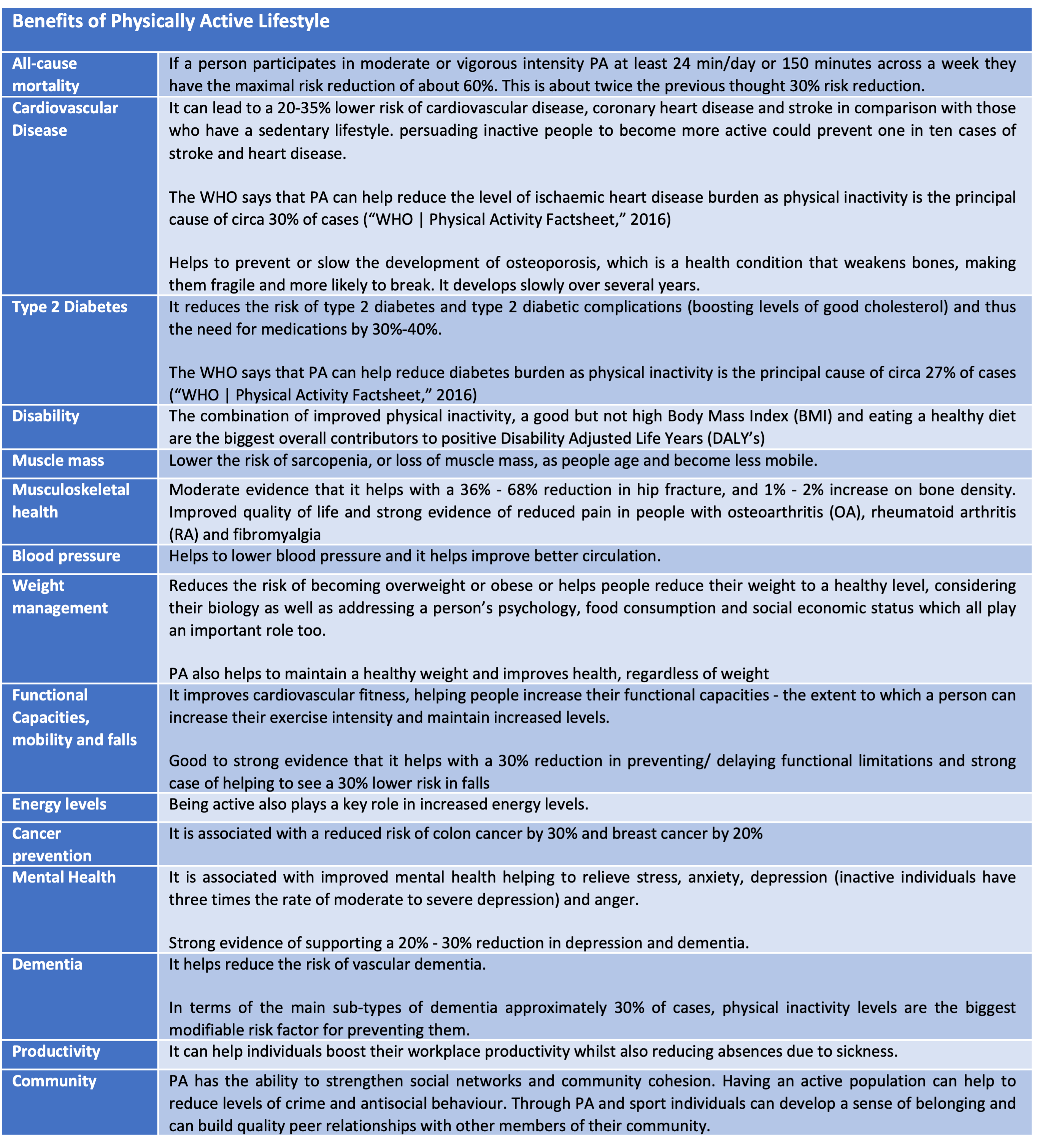

The benefits of PA are not only vast for the individual, but it is also the same at a societal level. On an international scale, PA has been recognised as a contributing factor towards 13 of the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 98. At a societal level, the higher the percentage of people engaged in PA can assist in tackling many of the important health and social care challenges faced by Wandsworth Borough and it can also have a positive economic impact. In relation to a positive economic impact, it is estimated that a 1% reduction in inactivity levels results in savings equivalent to £44 per household, and it also helps improve the health and well-being of the local community. The benefits of being physically active are summarised in the table below.

In terms of health, it increases peoples’ risk and likelihood of developing disabilities and diseases. Inactivity and sedentary lifestyles and resulting overweight and obesity are both associated with higher risks of developing chronic diseases such as coronary heart disease (CHD), hypertension, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and certain forms of cancer such as breast and colon. It can also lead to increasing / multiple co-morbidities and can reduce life expectancy 99. As you get older these risks become greater according to CMOs.

In fact, inactivity is the fourth largest cause of disease and disability in the UK 100. At worse, inactivity and a sedentary lifestyle are one of the top leading risk factors of death 101. For example, physical inactivity is responsible for one in six UK deaths, equal to smoking, and globally is the 4th leading risk factor for mortality accounting for 6% of deaths globally 102. Also, higher sedentary time is associated with a higher risk of death and that this risk increases at levels greater than 9.5 hours a day.

At a societal level, inactivity and sedentary lifestyles puts pressure on both tight local government and NHS resources and funding, making services unsustainable. Across the UK physical inactivity is costing the UK an estimated £7.4bn a year 103. For example, long-term conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular and respiratory disease not only increase hospital admissions and GP visits. It can also lead to greater dependency on home, residential and ultimately nursing care, which puts a drain on resources as well as the personal strain it puts on families, individuals, and carers 104. If current trends continue, and become more reflected in Wandsworth, the increasing costs of health and social care could destabilise public services and is likely to take a toll on the quality of life for individuals, carers and communities.

Importance of Targeting Inactivity and Increasing Impact on Health

According to the CMO, targeting and supporting inactive people to become more active, even if falling short of the recommended levels of activity, is where the biggest public health gains lie 105. Therefore, getting inactive people to become active has greater health benefits than getting active people to do more activity. This is something that will take time to accomplish. The best approach to reducing sedentary time and subsequently increasing total PA is to take small steps as this is likely to be achievable for the majority of people 106. This is supported by Sports England, Sporting Future Strategy where they maintain that we must have a stronger focus on tackling inactivity.

“Sporting Future makes it clear that in the past much of the action and funding supported people who would probably have been active anyway. It is important to ensure they continue to be catered for, however the biggest gains and the best value for public investment are found in addressing the people who are least active. This is based on scientific evidence. The figure below shows the value of getting people active from different starting points 107. It illustrates that although increasing the activity of an already active person (say from 200 minutes to 300 minutes a week) will benefit that individual’s health, it is nowhere near the benefit experienced by a sedentary person who takes up even a small amount of activity”.

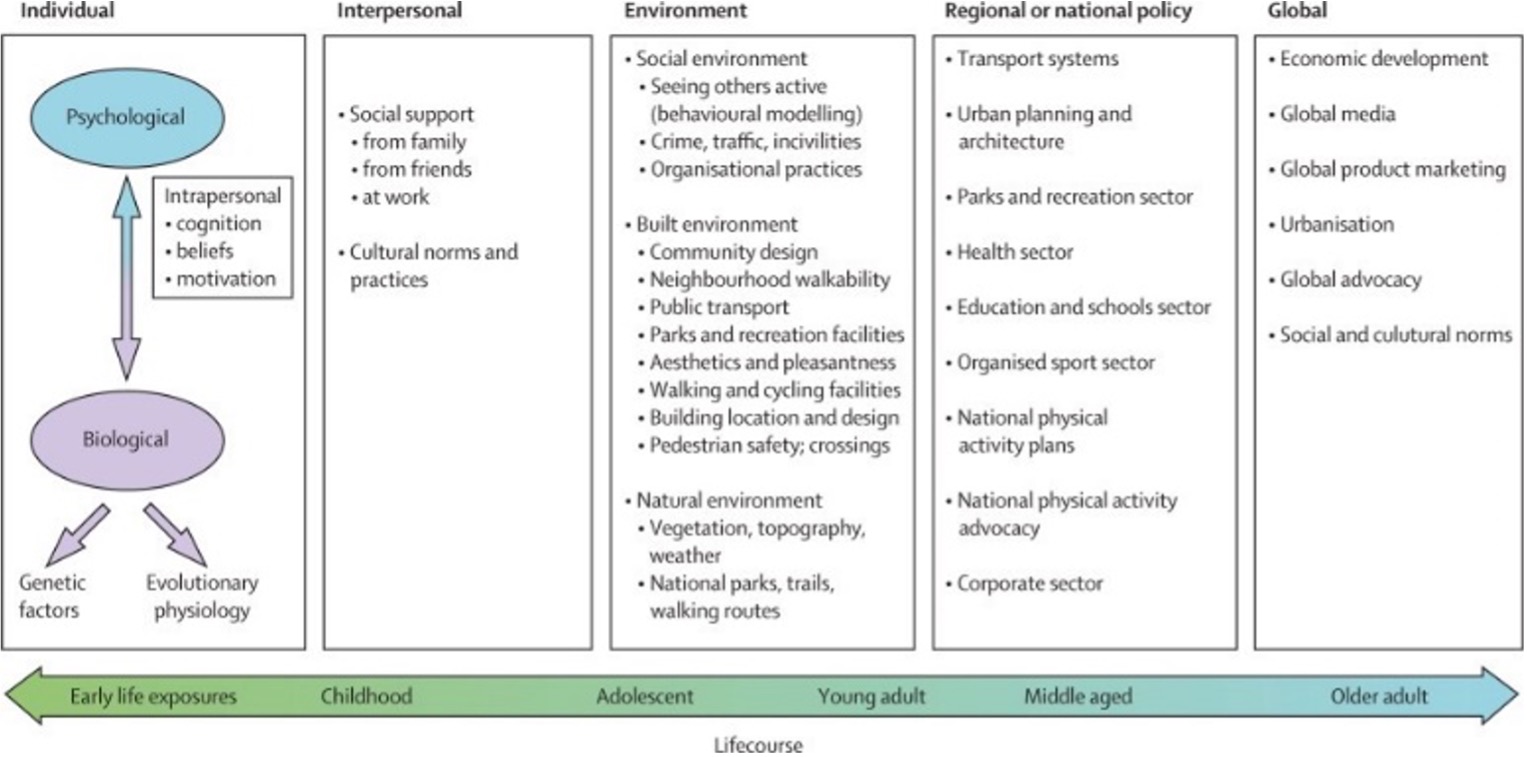

Source: Sport England Strategy 2016-21, Nigam 2011 108

The predominant focus in the past has been on individual-level factors. There is now a movement to focus more on determinants which are at the other end of the ecological model spectrum. They take a broader view of health behaviour causation, with the social and physical environment included as contributors to physical inactivity, particularly those outside the health sector, such as urban planning, transportation systems, and parks and trails. In addition, more recent research on determinants is now identifying genetic factors that contributes to the propensity of people to be physically active as well as evolutionary factors and obesity that might predispose certain people to inactivity. An understanding of correlates and determinants as advocated by the ecological model (the figure below) it is argued would reduce the effect of future epidemics of inactivity and contribute to effective prevention of non-communicable diseases.

Source: Bauman et al, Correlates of physical activity. The Lancet 109

4.3 Prevalence and Picture of Physical Activity

The Active Wandsworth Strategy 2017-2022 was put in place in 2018 to address inactivity by striving to make Wandsworth the most physically active Borough in London. Wandsworth needs to continue to build on the success of the Active Wandsworth Strategy (2017-22), which drew on a several key strategic themes with associated outcomes and objectives.

Adverse Impact of Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behaviours

Percentage of physically inactive adults: In 2023/24, Wandsworth’s rate was 16.4%, which was the 8th lowest in London, 25.2% lower than the England average and 27.6% lower than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2023/24 was also 4.7% higher than in 2015/16, in comparison with 1.5% decrease in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Physical Activity Levels in Wandsworth

Wandsworth had seen the number of people self-reporting as being inactive fall from 18.7% in 2015 to 13.6% in the period November 2018/19 Active Lives survey, but then rise again to 17.9% in the period May 2020/21 due to the COVID-19 pandemic 110. There was some improvement in the number reporting being only fairly active, 7.3% (May 2018/19) and more recently 8.7% (May 2020/21). Sport England also report that in 2016/17 Wandsworth had 82% participation in PA and sport at least twice in the last 28 days. This is much higher compared to London average of 77%. In addition, Sport England reports that, “Wandsworth has a greater percentage of people who are limited by illness or disability participating in PA than London” 111 . These are all encouraging figures, but it is important to bear in mind that these are all based on self-reporting surveys which have been known to be influenced by over-reporting or misunderstanding of what each category of intensity actually means.

In the period November 2018/19, Wandsworth achieved a significant 8.9% increase in residents being categorised as active compared to the previous year (Sport England’s annual Active Lives Survey). At that time, circa 79% of Wandsworth’s adult population, up from 69.3% in 2015 , achieve 150 minutes of PA per week – see the table below. This far exceeds London’s and the national figures of 64.4% and 63.2% respectively, representing a significant increase of 9.3% since measurement began in 2015.

Source: Public Health England (based

on Active Lives, Sport England) 112

Source: Public Health England (based

on Active Lives, Sport England) 112

Percentage of physically active adults: In 2023/24, Wandsworth’s rate was 74.8%, which was the 8th highest in London, 11.0% higher than the England average and 12.1% higher than the London average. The latest Borough figure for 2023/24 was also 1.4% higher than in 2015/16, in comparison with 1.9% increase in England’s rate in the equivalent time period.

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Source: OHID: Public Health Profiles

Physical Inactivity Attributable Factors for Poor Health